Thanks to Peter Parker (https://melbourneontransit.blogspot.com) for suggesting some content for this post.

++++++++++++++++

Much as Marc Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar came to bury and not praise the man, this post is not seeking to defend nor condemn. This post will go through both the events of the period but also the philosophy and outlook of Jeff Kennett and how it affected rail.

At the time the Kennett government and the man himself were very controversial, both in style and substance.

People had to deal not only with the chaos of the end of the Joan Kirner’s government and Jeff Kennett’s ascension, but the things happening in Victoria, Australia and the world generally, including simultaneous inflation and unemployment, which, as in the mid-1970s, caused personal heartache but social problems.

And it is personal. Unemployment in Melbourne and Victoria was so bad that this blog got to know the sunnier side of Queensland Rail, and then experienced Cityrail in Sydney from the perspective of being a working adult rather than a visiting teenager.

As such, it can be difficult to distinguish how much of community anguish, where it affected the railways, was caused by Kennett; or was simply visited on Kennett, or even that Kennett was trying to remedy.

The aim of this post to form a coherent view of the Kennett government and its rail policy. The passage of the decades does make it easier to be more objective.

Before Kennett: Cain and Kirner

When this blog reviewed the Cain-Kirner period that proceeded Jeff Kennett, it was seen as very much a mixed bag. For the government that proceeded Cain, especially under Rupert Hamer, had both presided over the destruction of much of the traditional VR country passenger network, and seemed destined to finish the job – when they undertook a massive reversal and started making some welcome investment in it under the banner of the New Deal for Country Rail.

For the Cain Government, it was sufficient then to build on this, reverse a few more of the Hamer cuts, and then rest on its laurels for the balance of its term.

In the suburbs, Hamer had started the process of updating the train fleet and building the City Loop, which Cain was there to consolidate without adding anything new (despite substantial plans promised from opposition but not acted on). At least it could be said that nothing was proposed to be closed, though by the end of the Cain-Kirner period it is not clear that even that could be held off indefinitely.

The freight network had continued to shed its branches and small pick-up services and was becoming limited to seasonal grain; interstate intermodal and some train-load specialist operations, though these too would be generally lost to rail by the end.

Credit as shown. Wahgunyah traffic lost.

Meanwhile the Cain-Kirner government continued the steady improvement of the interstate highway network, supported by Hawke federally, and this saw more stretches of the Hume, Western and Princess Hwy (east and west) replaced with freeway or duplication.

In summary, there was not much happening on the rail network and no strategic policy differences in place at the end of the Cain-Kirner period than there had been at the start, except that as the economy tanked serious questions started arising about the capacity of the state government to afford what it had.

Already the suburban rail fleet had been leased to an Austrian bank to provide some needed cashflow to the government. Stories appeared in the local newspapers that contractors to the state transport entities were not being paid in a timely fashion. This was not thought to be peculiar to rail – other government portfolios were having cash problems.

This was a different problem from the Hamer period – where the ‘microeconomics’ of rail was in question. It was inefficient and bloated with uneconomic operations. The network reduction was a response to this.

But at the end of the Cain-Kirner government, it was a ‘macroeconomic’ problem – the state government and economy not able to sustain the rail network with declining state revenues from such things as land tax, sales and stamp duty, while non-discretionary expenditures to do with welfare and job creation were blowing out.

Kirner had little in the kitty to promise when the 1992 election approached, however the need for replacements for the remaining non-airconditioned outer-suburban diesel trains was identified, with the solution being the Sprinter 7000 series self-propelled cars, which were on order but not delivered when the government fell. The impact of Sprinters on the Kennett era will be described more fully below.

In the late 1980s and early 90s, despite the New Deal, the ancient DERMs (from the late 1920s) and a small fleet of ex-South Australian Railways cars were still providing ‘interurban’ service despite their unsuitability, starting with their lack of air-conditioning.

Unlike the New Deal lines, there was no template for these services other than that some T class locomotives had been converted to P class, and Harris cars rebuilt for loco-haulage and fitted with air-conditioning, but clearly not enough of these. A curious but common match-up was to have a DERM haul a single air-conditioned Harris car, providing modern fit-out for those who wanted it.

Kirner had also overseen the purchase of a single set of what became called 4D – Double Deck Design and Development train. Intended as a prototype for a fleet of approximately 20 full-length sets which, due the financial crisis, was never bought.

Diversion Time: 4D

Despite clear derivation in bodywork from the State Rail Authority Tangara, it was not a Tangara, and electro-mechanically was more closely related to the existing Comeng single-deck cars.

It is not clear what was really intended for the full sets, had they been bought. They were to be confined to the Ringwood line and branches, which, at the time were the most heavily ridden and politically volatile due to overcrowding. Platforms and other structures were modified on this line to allow their use.

Wikipedia photo Zed Fitzhume

The idea of concentrating this fleet on one line was not a problem per se. The Comeng trains already on the Ringwood line could be redeployed, and make up for the holes in the rest of the roster caused by the sudden withdrawal of the last of the Harris cars. Or potentially start the withdrawal of the non-airconditioned Hitachi trains (a big mistake of a purchase if ever there was one).

For the full fleet, however, the question would be whether stations would need to be lengthened. The standard full-length Tangara set was 160 metres long, a whole car length longer than the longer bodied standard Comeng that ran as six cars at 140 metres. When 4D was coupled to a standard Comeng three set it was already longer than normal, but the stations had some margin and longer Harris or Tait trains had previously run.

Plausibly an alternative and new design for a Melbourne double decker could have been instituted, even just one based on the “V” interurban double decks that Comeng themselves were rolling out for the State Rail Authority, which could operate as 6 cars. That too would make a mockery of the 4D train and show it for the election stunt it was.

The original NSWGR double deck interurban had reliability problems, but the 20 year long production run and longevity of these trains means that by the early 1990s they might have been a suitable option for Melbourne trains, especially expresses on the Ringwood lines. NSWGOV photo

This train length issue by itself is not that interesting, but it does illustrate how the Kirner government had left an issue “hanging” in 1992 with no clear approach to solving it and no money available to do so.

In the short term, with declining CBD employment as the unemployment rate climbed past 10%, it was not going to be a major issue how to accommodate the crowds on trains, but when that reversed there was no plan in place.

Electing Kennett

Kennett was not elected until the end of 1992, and the recession that had been brewing since 1990 had been running for more than 2 years by this point.

Kennett famously ran heavily on the state of the economy, and the idea of Labor as the “Guilty Party” due to scandals involving collapsed banks and building societies, as well as the perception that the unions were out of control. Kennett pushed the idea of a debt crisis that needed radical action to solve – manifest as the idea of the Moodys Rating Agency “AAA” credit rating – that was lost under Cain and would need to be restored under Kennett.

Despite his own ‘dry’ leanings his Minister, Alan Brown, was a previous leadership contender and a bit more ‘wet’.

It should be kept in mind that even then the state government had very little to do with the macroeconomy and even the federal government had diminished influence once monetary, incomes and trade policies were put beyond its remit.

And it was federal Labor’s obsession with fiscal discipline that gave it little scope to intervene with useful things like capital spending, and left it to the ‘self-levelling’ features of diminished taxation and increased welfare spending to push the budget into deficit.

Larger effects also hit Melbourne and the provinces that were not directly the fault of state Labor. Tariff cuts and the Button Car Plan saw huge reductions in the manufacturing base; other microeconomic changes initiated by Hawke and Keating depressed spending on ‘real’ things while vast sums of money were drawn into financial speculation and asset inflation that made the top end of town very rich.

And finally, interest rates went through the roof to enable deficit spending to continue while West Germany unexpectedly had to borrow money (they had been net creditors) to repair the newly-absorbed East Germany.

West Germany had been advancing its rail system through the 1980s, while East Germany was in poor shape. Fixing this required borrowing from world markets and driving up interest rates.

None of which really mattered when it came to blaming someone. State Labor would do.

Little of Kennett’s agenda had any relevance to rail, with his main targets being the total number of public servants, the Education Department and other targets, some no doubt motivated by their involvement with Labor politics.

With rail, citizens would have got the sense that the major target was the unions, who had brought hell to the Cain-Kirner government. As the previous blog post outlined, this generally started with Minister Roper and peaking under the Ministry of Jim Kennan, who had introduced a ‘scratch’ ticket as a way of cutting labour costs, at that time, the large number of ticket conductors on trams and platform staff on the railways.

The Age photo of Lou Di Gregorio, from the union and nemesis of Kennan at his retirement

Scenes like this were seared into Victorians’ minds when it came to Cain and Kirner’s industrial troubles. Govt photo

While the Ministers’ individual personalities and the superficial issues they fought the unions over were no doubt important, bigger issues had been at play.

Federally, the nexus between union recruitment, industrial action and pay rises had started breaking down under the Accord of Hawke and Kelty. Federal Labor was pressuring for unions to amalgamate which would leave fewer deckchairs on the Titanic for the officials to occupy, and rail had at least three major unions.

And finally, the overstaffing that the railways had experienced through the Hamer period, now manifested as fewer trains to drive or shunt, meant the full downsizing of the rail workforce was beginning to show.

Kennett had no links to the union movement and therefore nothing to be lost from a fight.

Keeping the focus on rail, it is clear during the period that much of the industrial disputation involving rail staff was directed at broader industrial reforms by Kennett, rather than just a measure of the anger at changes on the rail system itself, though there was plenty of that too.

With unionisation of the rail workforce very high and the system still state-owned at that point, it made sense for the Labor and anti-Kennett forces to use the rail system as a political pawn in their fight. However, it could do little to reassure the public that the rampant fighting from the Cain-Kirner period had stopped.

Cost-Cutting

Kennett would later become known for balancing the books as well as cutting costs by privatising government services, and this thread will be picked up below. But in 1992 that was not the thrust, rather, lopping branches off the tree to cut costs was the priority.

It was as if Hamer, Lonie and the late 1970s had returned. Though this would understate Kennett’s differences from Hamer – Kennett was seen as aligned with the ‘hard’ or ‘dry’ or even ‘new’ right wing and their increasingly assertive so-called ‘Think Tanks” such as the Institute of Public Affairs or Centre for Policy Studies.

The Victorian Commission of Audit 1993 was the vehicle for justifying cutting back suburban and regional rail. In the suburban network, the fragile Alamein, Williamstown and Upfield lines stood there again in the firing line.

Talk again was of a core network, in other words, not those lines.

With the Altona line “saved” by being part of the Werribee route, and the St Kilda and Port Melbourne routes now running trams, they were not the target, and Sandringham, which had also been a target for previous governments, was part of a blue ribbon of Liberal seats and not likely to be closed.

Upfield looked the most vulnerable. Road builders had their eye on part of the corridor, and Kennett was keen to promote road building.

This linkage is no co-incidence. Right wingers and Liberals specifically have never seen any contradiction between centralised and subsidised road-building, inherently socialist, and their anti-socialist ideology. Rail was an easy target, but roads were to be cherished.

Diversion Time: Upfield’s brush with Kennett

The Upfield line had a sorry and silly history to this point. Opened in the late 1880s as an alternative route to Somerton, on the NE line, via Coburg, it did not survive beyond Coburg once the land boom had collapsed. However, the line was reopened to Fawkner as part of the suburban service and then back to the junction at Somerton as a curious and very uneconomic outer suburban rail motor service (though the physical junction was not reinstated) in the 1920s.

That service stopped in 1956 only to be reopened in 1959 to Somerton through Upfield. South from Upfield it was electrified for passengers; north from Upfield it was a freight line serving the Ford factory. This was to be the line’s second reopening or third opening.

By the early 1990s it stood to be closed again. With Ford no longer shipping cars by rail the Somerton-Upfield section had already been abandoned again in all but name. The passenger line ran parallel to a tram line for most of its length, and the area had been hit hard by the de-industrialisation of the Hawke-Keating era.

The line was unattractive as a rail line. North of Fawkner it was single track and capacity-constrained. It was not particularly fast, and had numerous level crossing gates of the old kind manned by crossing keepers. Coburg for many years had a single platform despite the surrounding track being doubled.

As in Kennett’s day, the Upfield line has become a touchstone for the far/old Left and community activism. GreenLeft photo

Complicating the Upfield line’s future was the rail corridor through Macaulay, which road planners wanted for the Citylink project, a freeway to be built from the end of the Tullamarine freeway at Flemington Road, to ultimately join the Westgate freeway before tunnelling under the domain to the Monash Freeway at Richmond.

Nonetheless a strong community campaign was launched and saved the line, with the freeway to go on pylons above it (which was likely always the plan)

Once the government relented, and volunteered $20m to fix it up, including automating the crossings and signalling, it was the nature of the paradox that the last traffic for the Upfield-Somerton line emerged.

PictureVictoria photo

When the section from Flemington Bridge to North Melbourne was ripped up for the freeway construction, the section between there and Upfield was run as an isolated shuttle service. To get trains in and out for servicing, they were hauled by diesel along the Somerton section. There have not been any trains since, and that section awaits the Network Development Plan proposal to restore it in the distant future.

Photo from Railpage – owner unknown

This article in the Age showed the paradox of closing the Upfield line. Referring to Alan Brown and the decision he had to make:

Alan Brown was transport minister in the Kennett government. He deferred the date of execution while a panel of planning experts assessed the best alignment for CityLink.

“When we became the government, Victoria’s finances were in a very parlous state, there’s no question about that, and we did look to where we could make change that was sensible and that would make substantial savings, but also we were conscious of the future of Melbourne’s growth,” Mr Brown says.Ultimately he chose to keep the Upfield line and build CityLink over the top of it, becoming an unlikely saviour of the chronically neglected public transport link through Labor’s heartland.

“There was really nothing in it for us politically,” he says. “It was a line that serviced electorates that the Labor Party held and would clearly continue to hold, but it was the right decision for Melbourne.”

In essence, Kennett turned Upfield from a problem into a political weapon against Labor.

Robin Cooper, the next Minister, said in his lengthy speech to Parliament:

She goes on to talk about rail infrastructure and a commitment to upgrade the Upfield line – that coming from a political party that tried so hard to close the line down. The only thing that kept the Upfield line open was the Labor Party’s belief that it would lose more seats than it did.

As with Upfield, so went the rest. Despite the threatened cuts, all the suburban lines survived. Services were reduced, particularly when the 1992 Christmas timetable (at which time services had previously always been fewer as people took holidays) became the permanent timetable, and was so for years.

Readers can make their own judgment about whether Brown’s and Cooper’s comments are self-serving. But condemning the Kennett government’s actions with suburban rail without considering the evidence is foolish, hence this blog post has aimed to explore them more fully.

The end of the New Deal

Things were not great for country rail – the damage done in Kennett’s time has still not really been undone, though arguably the country rail network of today has headed in a different direction from the New Deal and it is a position no sane person would want to return to.

Where Cain had restored service to Stony Point, Leongatha, Mildura, Cobram, Bairnsdale beyond Sale, and Dimboola as part of the Horsham day-train service, all of these were now at stake and more.

And yet, as with Bland, Lonie and other past cutbacks, the targets of the cuts were not immediately rationalisable down to patronage alone.

Brad Peadon photo of the Stony Point DRC

Elements of the Stony Point story are always odd, but thankfully this line did survive. The line had been on Hamer’s closure list and duly closed in 1981, to be resurrected in 1984.

Cain restored it with the DRC – airconditioned and comfortable – as shown in the photo above. This blog post makes the case that it was always in a position to be saved even in 1975, and with comfortable stock. Which was duly validated by what happened afterwards.

Unlike the similar small country branchlines around the state that closed, this line had been upgraded and well-used, at least to the Long Island Junction 2/3 of its length from Frankston, by heavy freights. Only the section beyond there needed restoration.

The line operates as a shuttle from Frankston (except for brief period under Cain, when on Sundays 2 direct loco-hauled trains ran from the city).

The top of the line was inadequately served, then and now. As in Cain’s day, a 90 minute to 120 minute frequency was inadequate for suburbanised Langwarrin, the Monash Peninsula campus and the outer suburbs of Baxter and Somerville. Further down the line the ‘interurban’ characteristics of places like Hastings, Bittern and Crib Point were more evident.

However you cut it, the Kennett Government thought it under-utilised, but community campaiging and allegations (not the only line in this category) that the Transport bureaucrats were understating its use, saw it saved in much the current format.

The DRC, as will be covered further, gave way to locomotive-hauled air-conditioned Harris cars, first with the T class and then the larger A class, before finally it ended up, as it is to this day, worked by the Sprinters. Only the current proposals to electrify to Baxter, go some of the distance to making the service genuinely worthwhile for the top of the line.

The line beyond Shepparton to Cobram, only recently restored. was again a target, but with low population and minimal agitation to reverse the decision (and in an area likely to vote Kennett back in, at least in those days) it stuck, and the last train ran in 1993.

John Cain reopened the Cobram service into Liberal/National territory. Unknown photographer, from Railpage.

The loss of the Dimboola train was felt hard, not so much at the terminus but in Horsham, Stawell and Ararat, much larger towns. The Ararat service lingered a few months longer but it too succumbed by the end of 1993. For a few years these stations remained available (at night) to Vline as broad gauge via the Overland (increasingly run by AN) but when this was converted to standard gauge and privatised by the federal government, the link was all but severed, and Stawell station closed completely.

The Bairnsdale line, beyond Sale, was closed after a spectacular event of activists trying to imprison the train which resulted in the Mildura service being cancelled early, on the extremely unlikely pretext of a ‘landslide’, perhaps mimicking Puffing Billy (?).

To quote the current Member for Mildura:

“The withdrawal of The Vinelander service in 1993 occurred under controversial circumstances. Two days before the service was scheduled to be axed, intending passengers were on the platform at Spencer Street station, ready to board the train to Mildura, when it was announced that it had been cancelled due to a landslide along the track. Despite the very short notice of the cancellation, buses were conveniently available as an alternative. Suspicions about the supposed landslide story were aroused when it was noted that it hadn’t blocked the Melbourne-bound Vinelander that same evening. A leaked document from the train controllers working that evening also aroused suspicion and an investigation revealed that the story about the landslide was a hoax. V/Line failed to give any clear explanation for their actions and it is widely believed that the sudden cancellation of the final Vinelander service was done to avoid any protests, such as the one that had taken place earlier at Bairnsdale, when the withdrawal of the service occurred as planned a couple of days later.”

Mildura is probably the town that still most heavily complains about the lack of service to this day.

Felt most heavily by rail enthusiasts, even if not by the locals, was the closure of the Leongatha service and ultimately the line itself.

Wilf Williams collection – Leongatha

Another Cain-era resurrection, using the P class plus H sets spoken of in this post, it can ultimately be argued this line had it all wrong even in Cain’s time.

The morning train to Melbourne could be used by commuters but the evening return, around 4pm, was far too early. The P and H combination was not particularly comfortable and lacked the amenities that the N sets had, even on some shorter runs to Geelong or Ballarat that ran in those days. The line itself was poorly aligned and maintained, and end-to-end journey times unimpressive, even when compared with the road which was also quite poor and even dangerous in those days.

A better option, though not necessarily as pleasant, might have been for the DRC to have worked shuttles to Dandenong, as in the temporary 1981 timetable, to get commuters from Cranbourne to the electric trains but then also operate say one long distance journey each day to Leongatha.

This graph tells some interesting stories – that trains are more popular than buses, but that potentially the demand that was came from the growing suburb of Cranbourne. And that the hard times that hit Victoria may have hit rural production communities like Korumburra and Leongatha hardest of all.

From DOI Leongatha Rail Line Review and Transport Assessment Options.

Perhaps this is what Kirner had in mind with the Sprinters when she proposed they run there – the flexibility to operate some suburban shuttles as well as a faster longer distance run. She did not stay Premier to see it.

Privatisation Part 1: West Coast and Hoy’s Bus Lines

Some more discussion of the merits of privatisation will be made below under Privatisation Part 2, however that will deal with ‘classic’ privatisation.

This first tranche of privatisation of country rail was entirely a different beast. The notion here was that two lines threatened with closure, namely the Warrnambool line and the Shepparton line, could be saved if operated by local small-scale operators.

In the Warrnambool case, it was by West Coast Railway, an entity connected with the long-running Bellarine Peninsula Railway and its people. It took a very different approach from the second operator, the local Shepparton bus line, though both sought to run their operations at a lower level of subsidy than Vline had previously received.

There were rumours, as there were from other lines, that the Transport bureaucracy was lying about patronage and revenue. Specifically, that the Warrnambool line might not be losing much revenue at all, or was even profitable.

Into this zone stepped the West Coast Railway.

While Vline would retain the rail track itself, the service would be operated by WCR locos and carriages. Fortunately for them, around this time the first of the air-conditioned long distance stock and mainline locomotives were becoming available for use by non-government operators. These included the B and S class diesels, and S and Z cars.

In most other respects the service was conventional, though probably it could be said delivered with a bit of extra ‘love’ from a company that actually wanted to run trains, not a disinterested and uninterested government bureaucracy.

In one sense this sort of privatisation did work. According to the Age:

Patronage grew by 20 per cent over the 11 years…[WCR Chair Don Gibson] said West Coast had been profitable, and the public had liked the service. “We delivered a lot of commercial benefits to the south-west through tourism,” he said.

It was finished off by the failure of the old locomotives and the constant closures of the line for the Bracks Government Regional Fast Rail project (for a future post).

The thing that really got the fans in though was not just the old streamliner diesels…but scheduled steam.

Martyn Bane photo. See this excellent site.

Though not always delivered, WCR aimed to have their steam locomotive R711 working regular Saturday return services to Warrnambool. This would be an ambitious program, as this would be a long distance to keep a locomotive running, fueled and watered. It really wasn’t the ‘enthusiast’ way of treating steam power – timings had to be much more like contemporary diesel practice, as this table from the Martyn Bane site shows, average speeds exceeding 100km/h.

Always popular, it lasted until the R class lost a connecting rod in a very unsafe situation which destroyed a cylinder. Almost an experiment, the WCR experience demonstrated that the public do actually like their trains; an operator who also likes them can at least cover costs; and that maybe steam has an attractive power.

Hoy’s, by contrast, ran a very conventional service, with the same Vline stock that Vline used but on lease.

Maintenance of the Vline service

As noted above, one of the last acts of the Kirner Government for rail was ordering the self-propelled Sprinters. These cars could work singly, or in long strings, and had a top speed of 130km/h, a record at that point for Victoria.

These were long overdue, but their arrival timing might have been better.

The DERMs and loco-hauled cars used on interurban routes were past expiry dates, while the DRCs, only 20 years old at this point, continued to be unreliable despite lots of work being done. Demand was also growing for passenger service to Bacchus Marsh, Sunbury and Craigieburn, though electrification funding would still be many years away.

And even on the New Deal lines, and despite the withdrawal of other services, the N sets had never been enough. Large numbers of the older aircon cars continued in service.

For a network trying to save money, the minimum deployment of staff to a loco-hauled N set train was four – two loco crew; guard/conductor and catering staff member.

The Sprinters arrival marked the opportunity to shrink the commitment to the remaining network. The Sprinters, sometimes even as singles or doubles, worked not just the local runs just past the electrified network, but also the longer ones to Sale and even Albury.

Though their seating was fairly Spartan and they lacked the catering of the N sets, they were fast, and brought a renewed image to country rail travel at a time when not much else good could be said.

Where they ‘headlined’ on routes to Geelong, Ballarat or Bendigo, they became the fastest trains on those routes despite the overall poor condition of much of the network.

Politically, they could therefore be seen as the ‘backstop’ to the notion that the network was going to just get worse. Kennett, having made the tough decisions to close whole routes, could at least be seen as trying to have the remaining railway put its best foot forward. And by the end of the period, non-airconditioned trains on the Vline network had become a memory, and frequencies on the interurban routes were improving.

Echuca and Cranbourne

In a time of slim pickings, the Kennett era actually saw the reintroduction of two train services where they had closed. They were quite distinct.

The Echuca service had been somewhat unexpected, though electorally explicable.

The last Echuca trains ran via Toolamba in 1981 and previously the passenger service via Rochester closed in the late 1970s as part of the tranch of Hamer cuts. In that respect was no different a dozen other lines, some with better claims to continue.

The new service was very thin, comprising a Friday service and Sunday service, allowing Melbourne people to go for the weekend, or Echuca people to come down. It was initially worked by a single Sprinter car – a risky proposition one would think, as by now you could not count on any diesel locomotives being in the area to rescue it. However it was well used, and later under Labor the service was improved to the current daily level.

Echuca nowadays. Techgeek on Wikipedia

The Cranbourne line came not long after the same station lost its service, under the same government, but in a very different format.

The Keating Federal Government, by now in electoral trouble, had provided grant funding under its Building Better Cities program to extend the electrification from Dandenong to Cranbourne.

While the transport bureaucracy had been keen to get this funding, even with the short-term expediency of using a diesel railcar, the Kennett Government was not keen to be spending any new money. However when the Federal money was touted as being basically the full cost, it gave Kennett an opportunity to be seen to be doing something positive while not bearing the financial repercussions.

The track, by now falling into poor condition as a marginal freight operation to carry sand from a quarry, was upgraded, electrified, with a new passing loop and two new stations constructed. In combination with a rebuilt station at Dandenong, it was just part of a very small amount of new investment in the Kennett period.

The sand train that kept the Cranbourne line in use beyond 1993, though it itself fell in the 2000s. John Dare photo

With such limited facilities, the initial service to Cranbourne was ordinary, but was better than what preceded it, which was 2 years of no service, and only twice per day before that. The suburban area quickly grew around it.

The line beyond awaits the day it is restored, though the Clyde extension project will probably involve ripping up the whole thing and starting afresh like at Mernda.

Experiments

Necessity breeds ingenuity, and Vline having no money for further orders of new rolling stock played around at the margins.

Weston Langford photo

South Australian Bluebird cars, by now not being used within South Australia for regular passenger traffic, were sourced for a series of trials on the Gippsland line to see if they could build up the capacity, especially with the passing of the electrification beyond Pakenham to Warragul. The trials were however unsuccessful as the cars were by now quite old and unreliable and did not result in a permanent service. Sadly many ended up as ‘crew cars’ of freight trains.

The RTL – a truck with rail wheels, was another brave experiment, one aimed at finding an economic way of moving small numbers of freight wagons around, with some flexibility about coming and going by road to get to them. The operator of country freight by now was Rail Victoria – owned by an American company.

The Bairnsdale line had in fact been all but closed by the mid 1990s, but late in the Kennett era it was reopened to limited freight use, but only the RTL was light enough and flexible enough to operate on it, until it was properly upgraded under Bracks.

Photo credited as shown – Dookie Line.

Stratford. Photo from http://www.hobbiesplus.com.au/gunzelgallery/rtl.htm

Again, in otherwise bleak times, the introduction of RTL created some interest for fans and some support to the idea that closed lines might one day be reopened.

Privatisation Part 2: The Classic Approach

The introduction of West Coast Rail and Hoy’s to the former Vline network was really just a bit of mucking around in the face of a campaign against closure while securing some cost reduction.

However by mid decade the bureaucracy, this time with several UK imports like Jim Betts (ultimately Secretary of the department) the idea of full blown privatisation was upon Victoria. Not just for rail, but for numerous government enterprises not least of which the electricity and gas, but also the TAB.

Profitable businesses could be sold for cash, thereby allowing debt to be paid down or new assets acquired. But with money-losing rail operations, the best that could be hoped for was to reduce the subsidy. The UK, with its more recent history of private passenger rail and replete with managers claiming skills in it, seemed the most likely model.

In microeconomics it is recognised that public sector inefficiency could be eliminated in the private sector, but having a private monopoly would only entrench these higher costs.

No real ‘on rail’ competition was possible, however, Treasury bureaucrats convinced themselves that breaking the metropolitan system into two separate operators meant they could have ‘rivalry’ [rather than competition] to reduce costs, and that smaller operators would appeal to a wider international market of tendering firms.

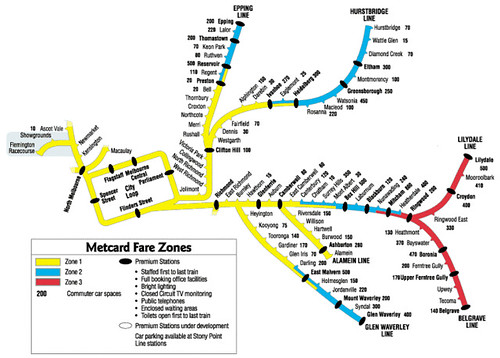

The result, fatal to this day, was to have the lines through South Yarra and North Melbourne called “Bayside” and the lines through Burnley and Clifton Hill called “Hillside” with the doubly ridiculous idea that the Flemington Racecourse branch would be also “Hillside”.

Thus started (though some of the ramifications of this did not become visible till after Kennett’s defeat) separation of rolling stock into incompatible fleets; a lack of system wide coordination; and even system maps not showing the other system’s routes.

Map doesn’t show the other network

Petty and pathetic overall. Again, though not wishing to spare Kennett the criticism he is due, this nonsense appears to have originated in the bureaucracy, specifically in Treasury and among its league of consultants.

The two operators, and Vline, were eventually privatised (though really only the management and operating rights) to National Express (M>train) and Connex (two up and coming UK operators).

Daniel Bowen photo

Promises were made about growing system patronage. Such claims were patently ridiculous at the time and much more so today. Operators and politicians even promised at extrapolated growth rates that the system would eventually be profitable, though for ti to be so, the passengers wouldn’t have all fitted on the trains.

Freight, as noted earlier, was sold first to an American operator, who had visions of buying more but was ultimately bought out by the larger national operators here. The sad story of country rail freight decline continued. This time, instead of just involving branch closures – most were gone by now – it saw the loss of traffics and yet more freight on road, such as the loss of traffics like sand on the Leongatha line.

Further cost-cutting – aimed at the unions

For the promises of privatisation to work, there had to be even further cost-cutting and specifically this meant removing the remaining suburban guards, instituting driver-only operation and electronic ticketing in lieu of manual tickets sold on stations.

Kennett thus bought into a further round of industrial conflict but this time on behalf of a constellation of different private companies rather than one megalithic government rail operator.

The unions, who had fought a courageous battle to hold on to the train and tram routes in Melbourne in the early 90s, were inevitably going to lose these battles. That was the point of privatisation.

Implementation of the schemes, especially Metcard, was haphazard, and started to eat into the myth of Kennett as a competent manager and this was especially because it started to affect the middle class who used the system daily to get to work. Not the occasional rural traveller or disadvantaged welfare recipient, but the core of the Kennett vote.

Daniel Bowen photo

It was also becoming clear that cost-cutting mantra, especially the “AAA” credit rating, was not resonating with the public as much as it had previously. Kennett exploited the “Guilty Party” idea again at the 1996 election and won it, but he wasn’t going to get a third round from it.

The end of the era

It is clear Kennett was a political strategist first, and only an ideologue second. Of course he surrounded himself with ideologues who were keen on both union-bashing and private enterprise, and both of these were in abundance during his government.

But his opening gambit wasn’t ideological, it was a political attack on the Labor Party, to disenfranchise them and tar them with the blame for the early 1990s recession and the scandals that marked the end of their government.

To do this, besides the propaganda, it was important to create a crisis; react to the crisis by, in this case, closing rail services and losing lots of people from the system. And to couple that to attacking Labor’s industrial base through the unions.

However by the second term Kennett was clearly in the ideological phase. Privatisation and cost-cutting was taking place not because it would undermine Labor, but because some in the government believed in it.

He was not a natural ideologue, and those in his broader party and movement who lead him down that path were one-trick ponies. And for a party that was going to appeal to the ‘broad middle’ that Labor had forsaken, they themselves were doing it.

As economist John Quiggin put it:

Advocates of commissions have learned nothing, and forgotten nothing, since Kennett’s audit 20 years ago, which in turn reflected the political orthodoxy of the 1980s, based on microeconomic reform, privatisation and financial deregulation.

But a lot has changed since 1993. Most of the useful elements of the microeconomic reform agenda have already been implemented. The idea that there are big savings still to be found after two decades of efficiency dividends, contracting out and corporatisation is an illusion.

As regards privatisation, the most important change has been in public attitudes. When Kennett began his privatisation program in 1993, the public was sceptical but advocates assumed that voters would be happy once they experienced the benefits. In reality, 20 years of experience has hardened scepticism into unremitting hatred. In Queensland, an amazing 85 per cent of voters opposed the Bligh government’s asset sales program. Not all of that was reflected at the ballot box, but enough of it was to reduce Labor to a handful of seats.

Of course, it’s open to advocates of privatisation to argue that ordinary people don’t know what’s good for them. But that claim sits very strangely with a rhetoric of free choice and individual responsibility.

Kennett was running into problems across his ministries, not just rail. Health and education had taken massive cuts and unlike rail it was hard for Kennett to keep blaming Labor and the unions for what was happening.

It is alleged that during some of the last Kennett cabinet meetings, Kennett himself was truly shocked at how badly some government portfolios were going and that Treasury and his own Department had been misleading him about this. This could be the sort of fairy story politicians might circulate to absolve themselves – or true. Or both.

Pursuing the debt and “AAA” had worked in the early 1990s to sow the sense of crisis, but it was hard to see in the late 1990s, with the economy well recovered, where the benefit of spouting ‘crisis’ was going to come from.

Unlike Hamer or Thompson, there was no Damascine conversion to improving rail transport as the 1999 election approached, nor were there any major promises made.

If anything, Labor looked slightly ridiculous for bringing up the subject of ‘fast rail’ to four provincial areas with only small amounts of money slated.

Kennett had foreshadowed the new suburban cars would be ordered – in fact this did not occur until after he was gone.

Labor was not looking any more electable than before and was fronted by yet another leader, the unknown Steve Bracks.

They had also promised to reopen lines closed by Kennett, a reprise of Cain’s move. In this case, Leongatha, Ararat, Bairnsdale and Mildura. It looked like Labor had not learned Cain’s lesson, nor (if history was a guide) would any such promise be enduring, as it had not been then.

Mildura is back to voting independent and hoping for the return of the train. Ali Cupper FB page

Labor, it turned out, was onto something: a provincial revolt Kennett did not see coming. The razzle-dazzle of Melbourne emerging from recession with roads, car races and casinos had not reached the country voters at all.

Some seats would never vote Labor but did vote for independents willing to do a deal with them. That could be traced quite directly to the four line reopenings – for which three of the independents stood – as well as for hospital issues in those same areas.

Ararat service eventually returned under Bracks

Labor also did pick up voters in Geelong, Bendigo and Ballarat, a sign that the Fast Rail pledge, though spurious to informed commentators, was resonating in the provinces.

Kennett might have been able to open the taps and start the spending again but it seemed to be against his nature. He had made so much of his fiscal rectitude. If the Libs had had any sense they would have dumped him, and put a ‘wet’ in his place to allow them to do exactly that. But he had been their messiah.

How to evaluate Kennett and his government’s approach to rail?

Of Alan Brown’s first Ministry, the Age, no fans of Kennett, had this to say [Robin Cooper in Hansard 1996]

We were led to believe it was not possible. The implicit message from the previous state government and the public transport unions was that the state’s transport service was as good as it gets … This week, the transport minister, Mr AIan Brown, announced that the service has halved its 1993 annual debt of $500 million. Since coming to power in 1992 the government has shed 9200 public transport jobs. Staff and debt reduction were always important in terms of efficiency but, in themselves, they were never going to persuade people to use a system that was unreliable, unsafe and inconvenient.

However, Mr Brown’s latest figures would appear to have made significant improvements on this score. …According to the Public Transport Corporation, train travel rose by 3.7 per cent in 1995-96, lifting the patronage level to the highest mark in 20 years. Tram use increased by almost 5 per cent, topping a 4.3 per cent rise the previous year … even the harshest critics should commend Mr Brown for taking on one of the toughest portfolios and bringing to heel the unions that had made it so tough.

The most creditable consequence of this political determination has been his success in bringing costs, previously regarded as virtually out of control, back to reasonable proportions … Mr Brown deserves to be congratulated … Commuters … are looking forward positively to the next stage.

At the end of the day, rail was no more than collateral damage from a campaign that was both political and ideological. At the start more political, at the end more ideological. Against which needs to be stated that any government, and particularly Kirner’s, would have been up against it trying to maintain services.

Not that the terminated country services really saved much money – note the amounts in the opening graphic from the Age in 1993: $5m for the Dimboola service, $3m for the Leongatha one. And no reference to the cost of the ones that were retained like Swan Hill or Sale. Systemic changes would have made more long run difference to costs than closing a service here or there.

Potentially the government, Kennett or Kirner, could have made more effort to keep all the services going, even if that meant cutting costs by using the Sprinters. They might have had to prioritise running them to the low-volume destinations like Cobram at the expense of not having them there for Sunbury or Craigieburn.

It was a credit to community campaigners that the Melbourne suburban system survived basically intact, because that was not what Kennett (or Hamer) had originally in mind.

Much of the deserved ire for Kennett really originates outside the rail portfolio, with cuts to healthcare and education more visible and real for many people. The rail cuts were probably more symbolic than real, except of course in those towns that lost rail completely.

It is clear when it comes to rail, his first term though so much more brash and abrasive than the second, is the one where he both settled down the industrial troubles that ran rampant under Labor but also settled the system at a more affordable level, albeit with some losses.

It was the second term where he went off the rails, so to speak, probably because he listened to bureaucrats who were selling the sort of snake oil someone of his ideological disposition was already warm to.

That Kennett was unable to extract himself from the ideological war he started, and reverse fiscal policy when the need for it had changed, was his personal and political failing. His abrasive style made enemies but it isn’t abrasiveness drives the need to make rail service cuts – but bureaucratic plans and calculations that are served up to justify it.

The weakness of the bureaucratic system is therefore the more enduring aspect of recent decades – that needs to function whether there is feast or famine.

Related: in 1996 backbencher Robin Cooper moved a motion congratulating the Kennett Government’s transport achievements during its first term in office:

https://wongm.com/2018/06/kennett-government-public-transport-improvements/

LikeLike

Thanks Marcus. I believe you have looked at Hamer on your blog – did you do Kennett too? It’s an interesting topic. I will do Bracks/Brumby at some point as well, a much more complicated subject.

LikeLike

My post about Hamer is here:

https://wongm.com/2017/04/hamer-government-public-transport/

I haven’t done a piece on Kennett yet.

LikeLike

Thanks Marcus. An interesting one, and more recent, would be to do Baillieu and Napthine

LikeLike

I recon the best thing that Kennett did was to reinstate the Echuca service and to increase rail and tram services on Sundays which used to be a 40 minute frequency. Now resembles the Daturday timetable. This was timely and stimulated tourism and dining out.

I regret the Mildura service was cut and even Bracksy who supported the reinstatement could not do so due to the condition of the tracks and they were privately owned. Also the less than cooperative nature of Freight Victoria later Freight Australia.

The Mildura service still has too many obstacles to it’s reinstatement to this day.

LikeLike

Thanks Daryl. Yes not sure there is much you ca do with Mildura service, might take 12 hours to get there and they have told the freight industry not enough paths (yet) so they would be angry if passenger trains took them.

They could honour their commitment to extend the Maryborough service to Dunolly (for the handful of passengers there!)

LikeLike